During the Soviet era, the Battle of Tehumardi and the monument were the subject of official, ideologically “correct” stories constructed by the political leaders of the party and the army. Estonian Red Army soldiers were portrayed as convinced Bolsheviks. However, to approach the monument and the experience of the rifle corps solely in terms of ideology is a fallacious approach.

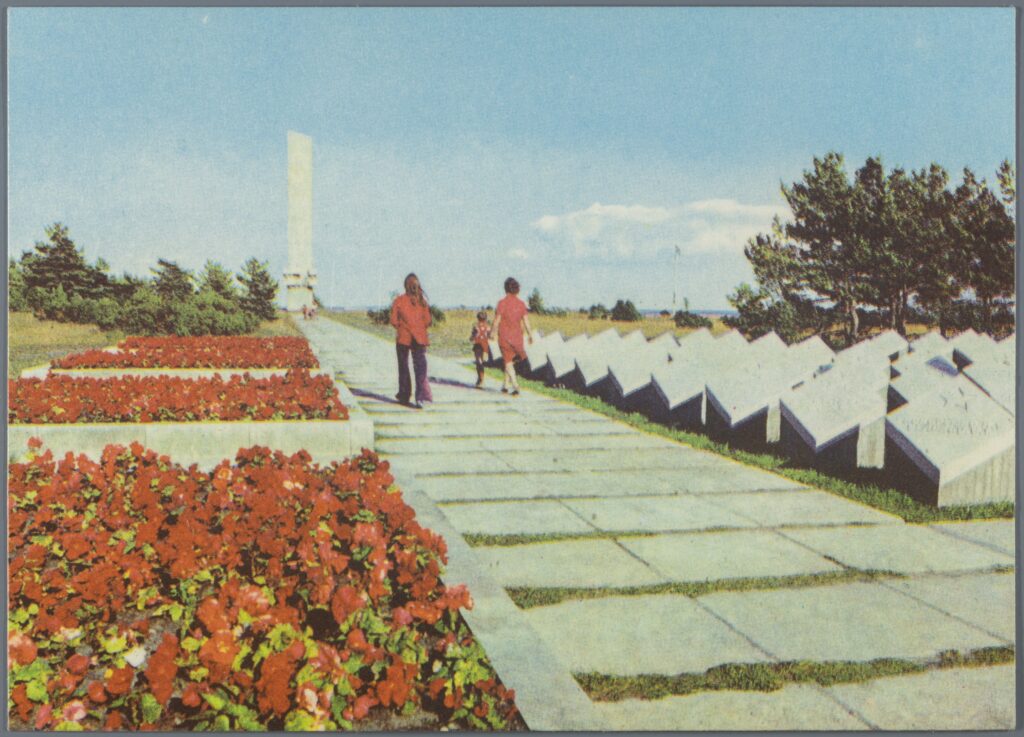

The Tehumardi monument is not just ideologised concrete and dolomite. It is also a place where the real battle took place, and with which veterans and their families associated their personal experiences and internecine struggles for decades. The battle was accompanied by legends, even a kind of folklore, which locals still tell today. For many of the combatants, Tehumardi became a place of sincere remembrance, a place to remember their fallen friends, brothers and comrades in arms, a place where they tried to give meaning to their lives and their destinies.

It is precisely this strange combination of ideology, nationalist-communist memory and organic life experience that makes the Tehumardi monument complex so important as a place of remembrance in Estonian history. There is no other place in Estonia or anywhere else in the world that can tell the complex story of the Estonian Rifle Corps – and do it on the landscape, not in a museum.

At a time when we are once again concerned about the threat from the East, an informed reminder of Soviet power – and not its censorship – is more important than ever. Tehumardi is a valuable reminder of how a totalitarian state sought to impose itself, how Estonian soldiers (and artists) were integrated into the service of a foreign power, and also how tens of thousands of Estonian men, almost half of the generation at the time, made sense of their complex lives under the conditions of the Second World War and the Soviet regime. They did so in different ways, sometimes applauding the ideology, sometimes deploring it, until at one point the public forgot all about them as being on the losing side of history.

Now is the time to rescue the history of Tehumardi from the Soviet ideologists warnings, the Russian Federation’s imperial retaliation and the oblivion that has befallen it in the post-Soviet era. The Tehumardi monument complex (which could include a memorial to German soldiers) is in itself a monument to the 20th century as an era of ideologies and its cult of war and sacrifice. Today, with appropriate historical explanations and stories, or with a possible transformative artistic solution, we can make the dolomite tell an even more instructive story: both of the tragic fate of the infantrymen and of Estonians’ wider experience of coping with 20th century ideologies.

Kristo Nurmis