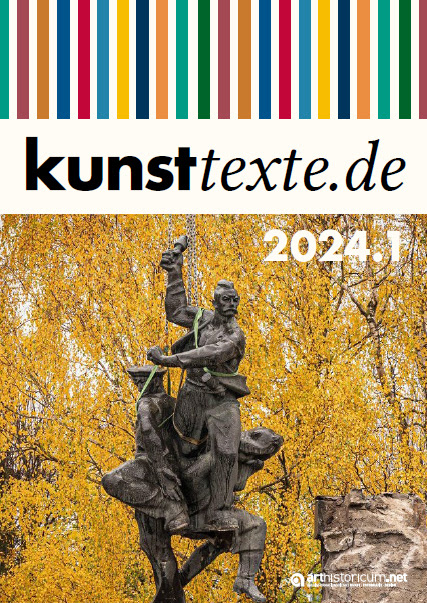

The special issue of the magazine kunsttexte.de, War on Monuments: Documenting the Debates over Russian and Soviet Heritage in Eastern and Central Europe. Documenting the Debates on Russian and Soviet Heritage in Eastern and Central Europe, edited by Kristina Jõekalda.

This issue of the open access online journal kunsttexte.de (https://doi.org/10.48633/ksttx.2024.1) contains 14 articles on the processes and debates surrounding the removal of Soviet monuments in recent years, placing what has happened in Estonia in a neighbouring and wider international context. A brief introduction to the special issue:

Many East Europeans probably have the impression that they know more or less what is going on with the monuments in neighbouring regions; that they know what kinds of debates about historical memory have been held in past decades. Do we really? Even if we did know, the situation has changed rapidly over the past couple of years. This special issue documents the recent and ongoing public debates about Russian and Soviet monuments in Eastern and Central Europe. The actions taken in terms of actual removal of monuments vary greatly. While in some countries a shift is barely visible, in others hundreds of monuments have been dismantled or relocated in a short period of time, and it seems that, behind these actions, political – rather than expert – decisions have been the guiding force. The focus of this special issue is the historical and art historical perspective on the statements about monuments by academics, heritage specialists, artists, journalists, think tank members and, of course, politicians. The 12 articles, some covering more than one state’s perspective, plus the introductory and concluding articles, offer a variety of analytical views on the developments in each country in a regional and wider comparison, documenting the professional, political and social reactions to the war in Ukraine as reflected in the public space.

Many East Europeans probably have the impression that they know more or less what is going on with the monuments in neighbouring regions; that they know what kinds of debates about historical memory have been held in past decades. Do we really? Even if we did know, the situation has changed rapidly over the past couple of years. This special issue documents the recent and ongoing public debates about Russian and Soviet monuments in Eastern and Central Europe. The actions taken in terms of actual removal of monuments vary greatly. While in some countries a shift is barely visible, in others hundreds of monuments have been dismantled or relocated in a short period of time, and it seems that, behind these actions, political – rather than expert – decisions have been the guiding force. The focus of this special issue is the historical and art historical perspective on the statements about monuments by academics, heritage specialists, artists, journalists, think tank members and, of course, politicians. The 12 articles, some covering more than one state’s perspective, plus the introductory and concluding articles, offer a variety of analytical views on the developments in each country in a regional and wider comparison, documenting the professional, political and social reactions to the war in Ukraine as reflected in the public space.

ABTRACTS

Editorial:

Historiography of Now: Russian/Soviet Monuments under Debate in Europe – Kristina Jõekalda 1–9

Many East Europeans probably have the impression that they know more or less what is going on with the monuments in neighbouring regions; that they know what kinds of debates about historical memory have been held in past decades. Do we really? Even if we did know, the situation has changed rapidly over the past couple of years. This special issue documents the recent and ongoing public debates about Russian and Soviet monuments in Eastern and Central Europe. The actions taken in terms of actual removal of monuments vary greatly. While in some countries a shift is barely visible, in others hundreds of monuments have been dismantled or relocated in a short period of time, and it seems that, behind these actions, political – rather than expert – decisions have been the guiding force. The focus of this special issue is the historical and art historical perspective on the statements about monuments by academics, heritage specialists, artists, journalists, think tank members and, of course, politicians. The 12 articles, some covering more than one state’s perspective, plus the introductory and concluding articles, offer a variety of analytical views on the developments in each country in a regional and wider comparison, documenting the professional, political and social reactions to the war in Ukraine as reflected in the public space.

1. The End of Spatialised Finlandisation? The Fate of Soviet Statues in Finland since 2022 – Olga Juutistenaho 1–10

This article examines debates related to Soviet statues in Finland in 2022. The war in Ukraine marked a political and cultural shift in Finland, as the country abandoned its previous neutrality policy and joined NATO. In terms of public space, this development was reflected in debates on and removals of Soviet-donated statues erected during the Cold War. In this article, discussions surrounding the World Peace Statue in Helsinki, and the Lenin statues in Turku and Kotka are used as examples. Standing at the centre of Finnish 2022 debates, opinions on these statues were divided: the public opinion was mainly in favour of removals, whereas several academics and other expert voices expressed scepticism. The debate was selective and focused on Soviet donations created by Soviet artists, while neglecting other Russian elements in Finnish public space. The removal of these statues is linked to the wider societal process of redefining the geopolitical position of Finland, functioning as a political stand in support of Ukraine, as well as symbolising a new era in the Finnish politics of memory. In many ways, the discussion can be seen as a belated reaction to the heritage of Finlandisation and the Cold War.

2. War in Ukraine and the Estonian War on Monuments: Contexts of a Discussion that Was Not Expected to Happen – Linda Kaljundi and Riin Alatalu 1–22

The article aims to both synthesise and contextualise the Estonian debates around Soviet monuments and other Soviet and Russia-related heritage since the full-scale invasion of Russia in Ukraine. The many regime changes in Estonia during the long 19th and 20th centuries have had an impact on the local monumental landscape and historical memory in this multinational border area. Emphasising the role of earlier post-Soviet monument crises, the article gives an overview of the dynamics of the most recent debates. It follows the emergence of both bottom-up and top-down campaigns to locate and remove Soviet monuments, as well as the governmental strategies: the founding of a secret monuments’ committee by the Government Office, and new legislative initiatives for the removal of Soviet symbolism. Despite the state authorities argument that there is nothing to discuss, the non-involvement of art and heritage professionals and undemocratic decision making gradually led to intense debates. Mapping the evolvement of a public debate between the professionals and the representatives of the state politics, the article also looks into the agendas of other stakeholders in this process, raising the question what was left out of the debates (e.g. the relative invisibility of Russian imperial and colonial heritage).

3. “History cannot be finished!” Dismantling and Demolishing Soviet Monuments in Latvia since 2022 – Maija Rudovska 1–12

The article analyses a number of processes that have taken place in Latvia regarding Soviet monuments since Russia launched a full-scale war in Ukraine on 24 February 2022. The Latvian government, in cooperation with several local organisations, has implemented a new law that has affected 70 monuments built either in the Soviet times or during the German occupation of Latvia during World War II. At the top of the list of monuments to be dismantled or demolished was the Victory Monument (1985), located in Victory Park in the Pārdaugava district of Riga. The article seeks to explore how these processes have been carried out and who have been involved in their implementation. It looks at the decision makers, as well as the context in which particular views were formed, by politicians, art experts or the society at large. Focusing on the controversies surrounding the monuments, the article specifically points out the politically charged decisions in the dismantling/demolition process, as well as the influence of the nationalistic discourse.

4. Decolonisation in Lithuania? Revisiting the Concept of Cultural Resistance under Foreign Rule since 1990 – Violeta Davoliūtė 1–12

The wave of anti-Soviet iconoclasm sweeping the Baltics has taken a somewhat unexpected turn in Lithuania towards a debate over the role played by writers and intellectuals during the Soviet occupation. A recently adopted law and associated political campaign to cleanse public spaces of the last remaining monuments associated with the USSR have collided with the plans of the Lithuanian Writers’ Union to erect a new monument in Vilnius to Justinas Marcinkevičius, a Lithuanian writer during the 1960s–1980s, and a prominent leader of the popular movement against Soviet rule. During the first wave of anti-Soviet iconoclasm in the early 1990s, a compromise was reached over monuments to Soviet-era writers and artists, leaving them untouched, for future generations to decide. Today, this compromise is being revisited, along with the notion that writers and artists who continued their work during periods of foreign rule were engaged in a form of cultural resistance. The outcome of this collision, in some ways intergenerational, is not yet clear. Will the iconoclastic impulse be channelled to help society work through the legacy of collaboration and accommodation with both the Soviet and Nazi occupational regimes? Or will it contribute to forgetting by erasing any and all reminders of this complex and difficult era?

5. The Borderline State: The Belarusian Frontier in the Memory Wars – Oxana Gourinovitch 1–12

The article examines the recent phenomenon of the Belarusian politics of memory, focusing on its unique mode of dealing with the legacy of Soviet memorials. This mode diverges significantly from the reaction usually associated with the post-Soviet region. The catalyst for this phenomenon was the fraudulent August 2020 election, which sparked unparalleled mass protests in Belarus, historically considered the “last Soviet republic”. For the first time in the Belarusian history, a great number of Belarusians felt courageous enough to embrace the vision of a de-Sovietised future. However, the segments of Belarusian society challenging the “Soviet”status quo did not follow the typical post-Soviet trend of iconoclastic actions against Soviet monuments. Instead, they positioned themselves as contenders for the legacy of Soviet remembrance practices, leading to their contestation across the Belarusian polarised political spectrum. By analysing events which were widely publicised on social media platforms or reported in popular periodicals, this article examines manifestations of this struggle, tracing its evolution from the onset of the 2020 protests to the present day. Furthermore, the article seeks to reveal the reasons for the enduring acceptance of Soviet monuments and memorial sites, which persist in Belarusian society irrespective of political affiliations. It delves into the intricacies of Belarusian national self-narration and its entanglements with memorial practices forged during the Soviet era.

6. Occupation and De-occupation of War Memorials in Ukraine: Commemorative Practices in Russian-Controlled Territories, 2022–2023 – Mykola Homanyuk and Mischa Gabowitsch 1–10

The article provides a concise overview of the Russian invaders’ interactions with war memorials in the occupied parts of Ukraine. Since the first days of the fullscale invasion of Ukraine, the Russian forces and proxy administrators have focused significant attention on war memorials in the newly occupied territories. They have claimed that World War II memorials in Ukraine have been either completely destroyed or left to decay. In reality, local residents in the northern, eastern and southern regions of Ukraine have often integrated Soviet-era memorials into the new Ukrainian national memorial canon and folk religious memorial practices in recent decades. Local residents have domesticated Soviet-era war memorials by installing additional, personal memorial signs and plaques, or by bringing religious symbols and objects to the sites. Since the beginning of the aggression in 2022, the most prevalent way in which the occupiers have interacted with war memorials has been by lighting eternal flames or marking existing memorials with Russian or Soviet symbols. In addition, they have engaged in iconoclastic practices, such as removing Ukrainian national symbols from the memorials. At the same time, World War II memorials have frequently served as venues for a variety of public events since 2022, ranging from legitimising the ongoing war to showcasing the commemorative efforts of diverse activists, including collaborators and political parties. As the Armed Forces of Ukraine have entered liberated territories, they have frequently singled out such monuments to install Ukrainian symbols, signifying the de-occupation of both these monuments and the lands. The comparatively few Ukrainian initiatives to have war memorials removed have been responses to Russia’s use of such memorials as pretexts for invasion.

7. World War II Monuments in Ukraine: Protection, Dismantling and Reuse since 2022 – Iryna Sklokina 1–15

The article concerns the different ways of dealing with World War II monuments in Ukraine since the start of Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Reevaluation, changing inscriptions, relocation, demolition and museumification have all developed around the notions of decommunisation, decolonisation, and de-Russification, in spite of the fact that World War II monuments are exempt from the “decommunisation laws”. The regions directly affected by warfare today demonstrate a more protective approach to World War II heritage as it is under threat of immediate destruction by the Russians. There is also a tendency to reinterpret these monuments in the light of the ongoing war with Russia and to use them for commemorations of the fallen in both wars. In other regions of the country, there are initiatives to change inscriptions and/or relocate the monuments from public space to cemeteries, but they concern only a small number of the monuments. The Lviv region in the west of Ukraine demonstrates a special pattern: the regional administration in concert with civic activists have effectively demolished almost all Soviet World War II monuments, in spite of resistance by, or lack of active support from, the local communities. Many civic activists and veterans are involved in the monuments’ demolitions. Rhetorically, the use of notions of “Soviet occupation” and the marking of Soviet monuments as “Russian” is widespread, as in other countries of Eastern and Central Europe.

8. Layers of Dissonant Heritage in Poland: Soviet and Russian Memorials after 24 February 2022 – Małgorzata Łukianow and Anna Topolska 1–14

This article aims to show the diverse avenues of the debates over Russian and Soviet heritage in Poland. While the Soviet monuments have been broadly contested – either as bottom-up or top-down initiatives – tsarist Russian heritage has been less visible in the discussions. In 2022 the country became a memory battlefield, adding layers to already palimpsestic memory sites. We provide both an overview of this process and a close reading of selected sites, concentrating primarily on the Monument to Heroes in Poznań and the Monument to the Liberation of the Land of Warmia and Masuria in Olsztyn. Moreover, this article looks at the role the Institute of National Remembrance has played since March 2022 in urging local authorities to dismantle Soviet monuments within their municipalities. The official removal of approximately 60 monuments across Poland is anticipated in the near future. 35 have already been dismantled by late 2023, sometimes following grass-roots initiatives. Our article examines this interpretive framework through the lenses of palimpsests and postcolonial theory. Characterised by the sequential actions of divulging and reinstating, palimpsests tangibly disclose latent historical imprints, while decolonisation endeavours to expose and revive suppressed narratives and meanings.

9. Colourful Transformations of Soviet War Memorials in Slovakia and the Czech Republic – Petra Hudek 1–16

Besides commemorating an important event or person, memorials have powerful communicative capacities. The difference between graffiti and memorials is obvious: graffiti is known for being provocative and not durable – it is ephemeral and emerges from the street, while monuments are erected “permanently”, often by a political power. From the perspective of protecting historical and artistic monuments, colourful graffiti may significantly damage them. Nevertheless, graffiti is a tool of protest, free expression and communication. Since 1968 citizens have often vividly expressed their feelings through demonstrations and street interventions in the form of graffiti and painting monuments, especially those associated with the Soviet Union. The aim of this paper is to analyse the function of the Soviet war memorials in the territory of the former Czechoslovakia in terms of their roles as communicators, reflected in the form of graffiti during both domestic and international crises and conflicts in the past half century.

10. “Alyosha, go home!” The Monuments of the Soviet Army in Romania and Bulgaria from the End of World War II until the Present – Claudia-Florentina Dobre 1–15

As a matrix of meanings, monuments are often at stake in the processes of appropriation or disavowal of the past, while preserving their status as marks of identity for the individual, the group, the city or the nation. This was also the destiny of the monuments built during the communist period in Bulgaria and Romania in order to glorify the “all-mighty Red Army”. Carved in stone, marble or bronze, and enshrined in the city landscape, they were celebrated constantly during the communist period. After the fall of the regimes, they were often vandalised, dismantled, or melted down, and became controversial. This article looks at the different stages of those transformations, focusing on the discussions and laws in the past decades. First the general situations are introduced in both of these countries, and then a few of the most intriguing case studies are reviewed in greater detail.

11. Memorials to the Red Army in Croatia: History, Preservation and Discussions since 1991 – Dragan Damjanović and Zvonko Maković 1–9

A number of memorials commemorating World War II fatalities or the military success of individual soldiers and units of the Red Army have been preserved in Croatia. They were built when Croatia formed a part of communist Yugoslavia (1945–1991), and can be exclusively found in its eastern and northern regions (Baranja, Slavonia and Western Srijem), where the Red Army played an important role in battles in the final months of the war. This article deals with ten such monuments: in Beli Manastir (two monuments), Vukovar, Ilok, Borovo Naselje, Markušica, Darda, Tovarnik, Virovitica and Batina. Only three of them are dedicated exclusively to the Soviet Army (the monuments in Ilok, Markušica and in the centre of Beli Manastir), while the rest commemorate the Red Army and the Yugoslav Army together. The most monumental is the one in Batina. Our field work has led us to conclude that the war in Ukraine has not significantly changed the attitude towards the Red Army monuments in Croatia: since the beginning of 2022, no initiatives to remove or destroy them have been detected. There are several reasons why there is less anti-Russian sentiment in Croatia than in some other parts of Eastern and Central Europe, and why the monuments have not become particularly controversial: the geographical distance from Ukraine; commemorating not just the fallen Red Army soldiers, but also the Yugoslav military units and local people; and not being erected by the Soviet authorities. Indeed, the monuments were often put up by Croatian or Yugoslav institutions, and executed exclusively by local artists. Finally, most of these monuments are legally protected as immovable cultural assets.

12. Contested Sites: Soviet Monuments and Memorials of Liberation in Germany since 1990 – Stephanie Herold 1–10

The article deals with Soviet memorials, especially those dedicated to the liberation by the Red Army in Germany. Using case studies of different objects, times and places, it highlights facets of the discussions on how to deal with these monuments, which took place mainly directly after the Russian attack on Ukraine, but which are still going on. In doing so, a link is not only made to the discussion that took place in the 1990s on the public treatment of political monuments of the GDR after the fall of communism. It is also argued that the monuments, which were erected with a clear political intention, now have different layers of meaning that accompany and shape today’s discussions and thus must also be taken into account in the further handling of this not only Soviet but also German local heritage.

Afterword:

Mimetic De-commemoration: The Fate of Soviet War Memorials in Eastern Europe in 2022–2023 – Mischa Gabowitsch 1–9

Some observers have claimed that Soviet monuments, and in particular war memorials, are coming down “across Europe” in response to the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Soviet war memorials have indeed been removed in large numbers in 2022–2023, even though previous waves of decommunisation had often spared them. However, the geography of this new strong iconoclasm is limited to Poland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and some regions of Ukraine, in addition to one case in Czechia and one in Bulgaria. This article analyses the new bureaucracies of iconoclasm, noting that they first emerged in Poland and then spread to new countries in a mimetic process. The article then reviews the actors and logics of monument destruction and protection. Whereas (mostly right-wing) governments and activists have spearheaded the removal of war memorials, the case to recontextualise monuments instead of removing them was primarily made by historians, art historians and heritage experts. The article dwells in particular on the ways in which Soviet World War II memorials have been appropriated and domesticated by local residents, gaining new meanings that go beyond their original ideological messages. It argues that de-commemoration, like commemoration, should be a complex process involving all those with a connection to the monument and what it memorialises, and that the top-down removal campaigns of 2022–2023 have largely eschewed democratic deliberation.