Pavel Petrov, a Master’s student in History and Eastern European Studies at the University of Helsinki, wrote this text as part of his internship at How to Reframe Monuments (July-September 2024) project. Besides publishing this and other texts on our blog, Pavel assists at the international workshop at Narva Art Residency.

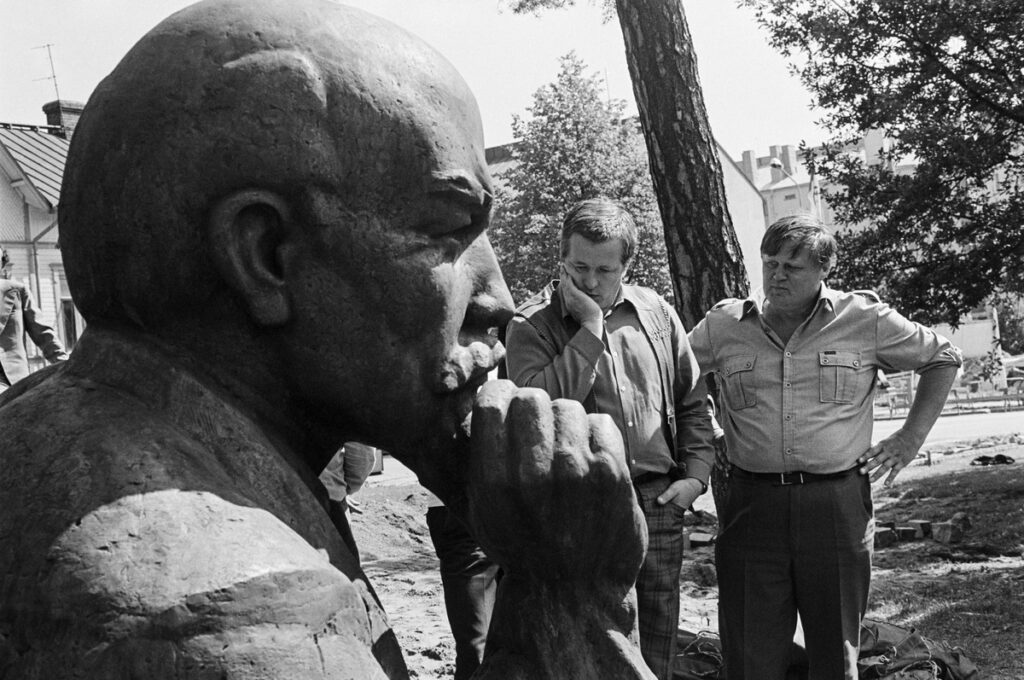

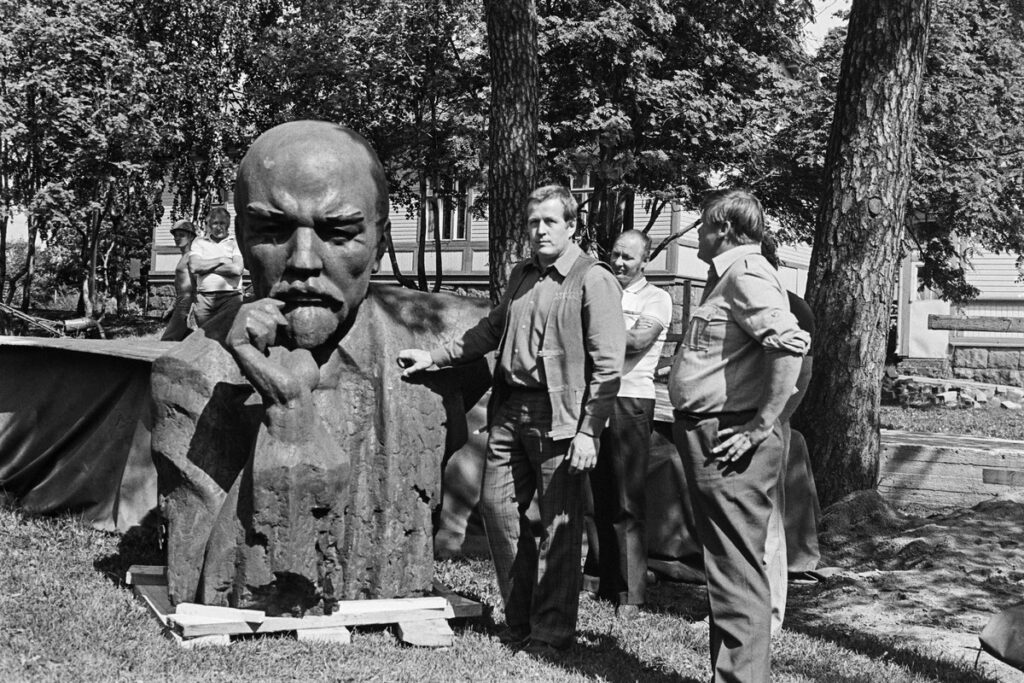

In 1979, the town of Kotka became the second Finnish municipality to receive a Lenin statue. As with the city of Turku two years earlier, the bronze-granite monument arrived as a present from Kotka’s Soviet sister city of Tallinn. The monument was designed by the Estonian trio of Matti Varik, Allan Murdmaa and Jan Poort. Varik and Murdmaa had also been previously involved in creating the Tehumardi war memorial (1967) on the Estonian island of Saaremaa and the monumental plaque of the Soviet Estonian writer Juhan Smuul (1972) on the wall of the Writers’ House in Tallinn. Both of these works by Varik and Murdmaa have been subjects to reframing measures. For Kotka, Varik’s cast a realistic yet quite unusual portrait of the Bolshevik patriarch. Projecting contemplating tranquility, the statue presented half of Lenin’s upper body with the right arm by the chin.

According to Kirsi Niku, the now-retired executive director of the Kymenlaakso region museum that covers Kotka, the form of Varik’s sculpture held a hidden meaning. In Niku’s view, the absence of the left arm was the author’s subtle way of expressing his opposition to both the Soviet ideology in general and the sculpture project forced on him in particular. This reading was shared by town councilors Joona Mielonen from the Left Alliance and Leeni Griinari from the Green League. However sustainable such claims and interpretations could be, the “missing” left arm of Lenin inspired the Polish artist Krzysztof Bednarski to make apparent the alleged subversion in Varik’s creation.

In 1995, the monument in Kotka received a surprising extension – Lenin’s Missing Arm created by Bednarski. As the name suggests, it portrayed the left arm of Lenin that completed the main portrait, when seen from certain angles. Bednarski cast the sculpture in bronze and put it on a separate pedestal close to the original statue as if a commentary on the margin. The timing for that might appear symbolic. Finland just joined the EU thus decisively breaking up with Finlandisation, or Soviet political influence of the past decades that produced inter alia the Lenin monuments in Turku and Kotka. With that in mind, Bednarski’s work embodied the new ways in which Finns could and did discuss Lenin in public after the the Soviet Union disappeared from the map.

What made Bednarski’s creation particularly remarkable is an almost burned cigarette held between the fingers. Lenin abhorred smoking and this sculptural commentary was clearly a mockery of the Soviet leader. In the author’s words, the cigarette looked like the “last smoke before execution”, which suited the pondering facial expression of the portrait. Bednarski also mentioned that his work, being smaller in scale and more human-like, also diminished the main statue. In that sense, the Missing Arm provided the ensemble with a slightly surrealistic and carnivalesque air. Simultaneously, Bednarski’s sculpture clearly implied that the original monument would remain in place even in the long term. Indeed, the new sculpture was said to stimulate public interest for the previously mostly ignored yet at times defaced composition.

Still, even this subversive and ridiculing reframing addition to the Soviet monument proved insufficient to avert its entire removal. Several initiatives in the spring 2022 proposed to remove the Lenin monument in Kotka as offending the memory of victims of Soviet crimes. Finlandisation was touched upon indirectly through reflections on “statue diplomacy”. Proponents of the removal claimed that donating the monument was originally a gesture, the purpose of which was to dominate both Tallinn who had to deliver the present and Kotka who had to accept it. They suggested that the monument in this case was an active measure to dominate or subjugate Finland.

However, such a one-dimensional approach ignores the critical fact that the monument in Kotka was a part of the Finnish-Soviet “statue diplomacy”. For Finland, accepting Soviet monument donations and creating its own pieces to celebrate relations with Moscow, constituted a tactic in the country’s Cold War survival strategy. In this respect, a presumed symbol of domination served in a paradoxical way as a means for Finland to maintain and promote its fragile independence, however compromised it was by the shadow of the Kremlin.

Emphasis on the complex past represented by the Lenin monument was central in argumentation by the proponents of preservation, as with Kirsi Niku from the Museum of Kymenlaakso. On the behalf of the museum, she said that it would be better to keep the monument at its original location for the benefit of future generations. Concrete solutions for additional reframing were presented by the earlier mentioned councilor Mielonen. In an attempt to keep the monument displayed publicly, he proposed to equip the site with information boards to explain the art object’s intricate history and significance, as well as to appreciate the supposed criticism of the Soviet regime by the author. This approach to amending the debated object was also preferred by the Museum of Kymenlaakso. Nevertheless, only less than one fifth of the representatives voted in favour of Mielonen’s initiative. The removal camp prevailed with their aim achieved in late October 2022.

The statue of Lenin by Varik together with the Missing Arm by Bednarski were transported to the Museum of Kymenlaakso’s storage for preservation. Bednarski did not oppose the removal of his work, because in his view the sculpture would not make sense on its own. Simultaneously, he expressed a hope that Lenin’s Missing Arm could be displayed at the museum thus reminding about this part of Kotka’s history. The Lenin statue was in turn offered to the Lenin Museum in Tampere, whose history and situation deserves a separate article, but was declined. Thus, both Varik’s and Bednarski’s works remain in the Museum of Kymenlaakso’s possession. However, the current location of the Lenin statue is classified with access restricted even for scholars. Such drastic measures have been explained by privacy and preservation reasons to rule out eventual defacement attempts.

Hidden from both public and experts, Varik’s work might remain in the secret storage for several years. The Lenin monument of Kotka survived the dissolution of its origin country and even “grew back” the “missing” left arm a few years thereafter, thus acquiring a new meaning. Yet this reframing intervention proved futile to keep the ensemble in place when Russia resumed its aggression against Ukraine in 2022. Perhaps, this bronze tool of “sculpture diplomacy” will have to wait for the next generation to grow up for whose benefit the Museum of Kymenlaakso has advocated the Lenin monument’s continued public display.

Pavel Petrov